In 1873, vestiges of the original owners of south central Wisconsin, the Ho Chunk — known as the Winnebagoes outside the tribe — still roamed public domain land which had not yet been privatized by the federal government. Steadily and gradually they were rounded up and transported in box cars to Nebraska. The following account is from the History of Columbia County, written in 1914.

When, in 1837, the Winnebagoes disposed of all their lands east of the Mississippi to the United States, they stipulated that within eight months they would move west of the great river. As many of them delayed their departure under various pretenses, several forcible removals were effected by the Government working through the United States of America. The last of these enforced departures occurred two days before the Christmas of 1873. Early in the morning of that day Captain S. A. Hunt and ex-Sheriff Pool crossed the old Wisconsin River bridge at Portage, heading a detachment of United States troops. The little expedition was bound for the Baraboo River, where, near the Crawford bridge, a considerable number of Winnebagoes had gathered for a feast and an annual meeting.

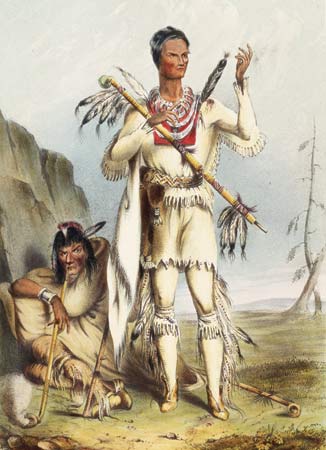

Almost every lodge for forty miles around had its delegate. The Winnebagoes (Bagoes, as they were called) had pooled their wigwams, their feathers, their paint, their wampum, and were having a hilarious time when their pow-wow was interrupted by the appearance of the uninvited boys in blue. Of course the greatest consternation prevailed, for the Indians knew at once that they must follow the bulk of their tribe to the reservation in Nebraska. A parley followed, and as the Bagoes refused to be persuaded by mildness, they were surrounded by Captain Hunt’s men and made prisoners to the number of nearly a hundred.

With as little delay as possible the captives were arranged in marching order and just before noon, with their families and all their festive paraphernalia, sullenly wound over the hill near the Catholic Church, escorted by the United States troops. They were marched to the depot, safely lodged in the cars, and a full supply of rations dealt out to them. After they had been housed, Captain Hunt set about to inform himself whether any of his captives had become real estate owners, or had done anything else to show that they had abandoned their tribal relations and were entitled to remain as citizens. Inquiry was made for Yellow Thunder, Good Village, War Club, Snake Swallow, McWima and Pretty Man, but it was found that only two of them were among the captives and they were allowed to depart. John Little John and High Snake were taken with the more common Winnebagoes. Although not legally entitled to remain, as their characters were quite warmly upheld by a number of respectable citizens, they were informed that they could return to Columbia county later, if they so desired. The ponies and all the other “traps” belonging to the Indians were then collected and loaded into the baggage cars, and at 6 o’clock the train was under way for Sparta, Monroe County, which was to be the point of rendezvous for all the Winnebagoes gathered in by Captain Hunt, who was the official government agent for the removal of members of the tribe who still remained in Southern Wisconsin.

Sunday and Monday were busy days and nights for ex-Sheriff Pool, his specialty being the collection of the squaws and families of the Winnebago braves who had not accompanied their lords to the Baraboo celebration. A writer of that time and event puts the matter thus: “As an Indian dance is very like a white man’s frolic in some of its characteristics, it was not a matter of surprise to learn that a number of braves were alone at this dance, while the squaws were doing the menial work of housekeeping at home and attending to the papooses. Now Big Jim was just one of that kind, and several others might be named, but out of respect for their families we will not put their names in print. The circumstances, however, made it necessary for Captain Hunt to dispatch Mr. Pool and other messengers, for their families, which were at Briggsville (Marquette County, just above, the Columbia line) and other places. By Monday evening Mr. Pool had two or three dozen of them congregated here, and on Tuesday evening they were forwarded to Sparta.” It would thus appear that the Christmas festivities of the Winnebagoes were rather rudely disturbed in 1873. As we have seen, their beloved and venerable chief, Yellow Thunder, remained in Columbia County and died in the year following the last forcible removal of his people.

As remarked by the late A. J. Turner, who has made such valuable contributions to the history of Columbia County, “this region continues to be the abode of straggling bands of them, from whose camps the descendants of De Korra, Yellow Thunder and Mi-ja-jin-a-ka (Dixon) annually depart for the blueberry plains and cranberry marshes to replenish their finances, to trap rats on the Neenah in season and indulge in fire water out of season, but give no evidence of ‘passing away.’ Lo is with us to stay.”

Next time you see the cliche black and white film scene of a steam train filled with Jewish prisoners sent to concentration camps in box cars, visualize that same setting with Ho Chunk families seated on the floors instead. Apparently Captain Hunt’s orders and mission did not include authorization to purchase passenger tickets. Since the account does not provide the details, we are forced to imagine them — the Ho Chunk families sitting on the hard splintered freight floors, in uninsulated cars, shuttled slowly around rail yard sidings as the cars transferred between the lines of different railroad companies, mostly in the dark since it was the shortest days of winter, everyone frustrated but probably no one more than the parents of the hungry, bored and restless children.

In 1840 the population of Wisconsin Territory was 30,000. By 1870 it was over a million. Needless to say the political and cultural character of the state and the people changed dramatically in that 30 year period. The 1870s and this particular event were turning points. Indian wars still went on, but in the far West — the Battle of the Little Bighorn was in 1876. It was also a time when post-war cultural optimism among Americans of European heritage was in rapid ascendancy, creating a sense of Americana. The first college football game was in 1869, and the National League (baseball) was founded in 1876.

Wisconsin remains a complex mix of Indian cultures. The fate of the Ho Chunk was very different than the fate of the Menominee and the Ojibwe, who both have large vibrant presences in the state well into the 21st century. Wisconsin was also the place where refugee Indians from New York (Oneida and Munnsee) were themselves relocated, and these nations are also well-established.

There are many reasons why the Ho Chunk were forced to move while their cousin tribes were not, but one of the most important was a legacy of fighting against Americans in the War of 1812. The tribes who allied with the British were not all at once forced to relocate, but their alliances with the British set in motion a chain of events which led to that. Canada was British territory at the time, and it was close enough that they meddled a good deal in the sovereign affairs of the United States, using various tribes as proxies. Black Hawk’s band of Sauk Indians, who fought the last war east of the Mississippi in 1832, were known as the “British Band” because they would travel from the village near Rock Island, Illinois, to Fort Malden in Canada near Detroit to get gifts from British agents.

The situation for the Ho Chunk was different from the Sauk only in respect to the fact that they did not have active contact with the British, but what the Ho Chunk had in common with the Sauk was lingering mutual distrust with the United States. A minor rebellion in 1827 led by Red Bird, fomented by this low-level animosity, is what led to the uncompromising position of the federal government that the only answer to the “problem” was to remove the tribe west of the Mississippi. Until the removal was completed, and even afterward, the Ho Chunk suffered miserably. In the book Waubun, Julia Kinzie has some very graphic descriptions of Ho Chunk families begging for bread in the area that is now Dane County.

After these forced removals, individuals did come back and got land in small ownership plots, sometimes by homesteading, sometimes by purchase, and sometimes in inter-tribal refugee camps deep in the north woods. However, they never reacquired even a vestige of large-scale tribal land. When Jean Nicolet first met the Ho Chunk in 1634, there were thousands of tribe members in villages from Green Bay to the Mississippi. There are less than 1000 in Wisconsin now. What does this mean and what do we do about it now? I’m not sure. However I think these are important stories that need to be told.